This is an excerpt from a new book published by the University of Wisconsin Press: “Tommy: My Journey of a Lifetime,” by Tommy G. Thompson and Doug Moe. It’s the life story of Wisconsin’s longest-serving governor, first elected in 1986, and his time in Madison and Washington, D.C., where he served as national health secretary in the aftermath of the 9-11 tragedy.

Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. ©2018 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.

Buy the book: https://uwpress.wisc.edu/

Around that time—December 1985—Kenyon Kies, who was managing director of the Wisconsin Utilities Association, had a holiday party at his office in downtown Madison, and across the room I spotted Jim Klauser, who had encouraged me to forgo a run for governor in 1982 and position myself for 1986. At that moment there was probably no one in Wisconsin whose political abilities I respected more.

Around that time—December 1985—Kenyon Kies, who was managing director of the Wisconsin Utilities Association, had a holiday party at his office in downtown Madison, and across the room I spotted Jim Klauser, who had encouraged me to forgo a run for governor in 1982 and position myself for 1986. At that moment there was probably no one in Wisconsin whose political abilities I respected more.

I waited until I saw Jim walk into the kitchen to refresh his drink. I followed him.

“Jim?”

“Yeah, Tommy.”

“I’m running for governor, and I need your help.”

“Tommy,” Jim said. “You don’t want to run.”

What Jim was really saying was that he didn’t want to get involved in another political campaign. His lobbying business was becoming very successful. He had just helped push through an important bill for Exxon, and new clients were knocking on his door. Jim was tired, looking at even more work, and felt the last thing he needed was to sign on to my run for governor.

I knew all that, but I also knew I needed him. We had received a report the first week of December from Brian Sweeney, a Republican campaign consultant, essentially an analysis of what my campaign for governor needed to be successful, and his top recommendation was that it needed to be run more professionally.

That evening in Kies’s office, I said, “Yes, Jim, I am running.” I said again I needed his help.

Klauser began to list the reasons why he couldn’t help, and I stopped him. “Think about it over Christmas. I know I can win, but I can’t win without you.”

In early January, Klauser came to see me in my assembly office. “I’ve made my decision,” he said. “I am going to support you. I think you can win. What do you want me to do?”

I said, “I want you to run my campaign.”

“I am not going to run the campaign, Tommy. I don’t have time.”

Instead of pushing him, I figured it would be better to just get him onboard in some capacity. If that happened, knowing Klauser, he might end up running things anyway.

I said, “You know what I would really like you to do? Make damn sure I don’t go into debt.”

I knew that would resonate with Jim. He had talked to me about Jack Steinhilber, who ran in the primary for Bill Steiger’s congressional seat—the one Petri won and I finished second—and Jack had been caught up in the race and found himself something like $35,000 in debt when it was over.

I told Klauser, “I don’t have any money. Very few assets. I’m putting it all on the line with this race. I won’t have the assembly seat anymore. I won’t have much of a law practice, after spending a year campaigning. If I’m in debt, I don’t know how I will ever pay it off. I’ve got three kids. They’re my first responsibility. I can’t go into debt.”

Klauser nodded. “OK, that’s my job.”

Jim was onboard.

He and his wife, Shirley, were in my assembly office the morning I made the official announcement of my candidacy. Jim has said since that I was nervous, but I think it was more that I was excited. It was April 6, 1986. I was practicing the speech in my office. Marlene Cummings, who later became my secretary of regulation and licensing, introduced me on the assembly floor at the capitol. I gave my speech and then I was off on a whirlwind two-day tour of the state.

That first day, after the announcement, we hit Mauston, La Crosse, and Milwaukee and wound up at Cliff and Ceil’s, a restaurant and ballroom in Green Bay that has since closed. A group of builders—builders were among my earliest supporters—was meeting there that night. The next day I was in Rhinelander, Wausau, Superior, Eau Claire, and finally back in Madison, for a rally of my supporters at the Badger Bowl.

It was a great two days. I enjoyed it and fed off the energy of the people who came to see me. I was an official candidate for governor. We had crisscrossed the state in those two days, and that would continue. Occasionally a private plane would be made available for the campaign, but more often we drove, and therein lies a tale.

Back in December, I had received a letter that meant a lot to me at the time and later had a greater impact on the campaign than anyone could have then known.

It was written by John Tries, president of the Milwaukee Police Supervisors Organization. He was writing to tell me his organization was supporting me.

“Our organization has never given its endorsement to any candidate in the past,” Tries wrote. “We are extremely impressed with your past accomplishments and your plans for the future.”

I was grateful, and Tries was to become an important part of that first run for governor. John was a big, tough guy, a Milwaukee police sergeant who was a native of Austria. He had recently injured his back to the extent that he went on disability from his police job. As I remember it, he was tossing his riot gear in the trunk of his car, moved the wrong way, and ripped some vertebrae in his back. In any case, he wasn’t working, and he said, “I’ve really got nothing else to do. I will be your driver.”

I said, “You’re kidding me.”

“No,” John said. “I want to help you win.”

He helped, all right. I had a 1984 Buick with maybe twenty-five thousand miles on it when we started the campaign. It was the only asset I had that was paid for. By the end of the campaign it had over two hundred thousand miles on it. John put most of those miles on that Buick, and I read or slept in the seat next to him. He was a warrior.

He was also fun to travel with. John liked Jimmy Buffett songs, and there is a Buffett lyric that describes “good days, bad days and going half mad days.” That’s what a campaign is like. I recall we arrived late one night at a motel in Sheboygan—we always slept in one room with two beds to save money—and John was checking us in, using my credit card. I came shuffling in as they were finishing up.

“Who are you?” the desk clerk asked.

“I’m Tommy Thompson.”

The desk clerk looked at John, pointed at me, and said to John, “Do you know his name is on your credit card?”

Another time, in Racine, the campaign had booked us into a terrible hotel that was located above a tavern. A band was playing and we couldn’t sleep. There was no question of going somewhere else—there wasn’t money for that. So we got through the night, and in the morning, when John was taking a shower, the bathroom ceiling collapsed. Everything, including John, was covered with plaster.

I think John’s favorite moment in the whole campaign came in a motel room in Waupun when he noticed a little laminated card next to the phone that said, “Please do not pick up this receiver unless it rings.” I don’t know what it meant unless they didn’t allow outgoing calls. John thought it was the funniest thing he had ever seen. Don’t pick up the phone unless it rings! John took the card with him when we left and kept it with him in his wallet until the day he died, which came too early, in 2006. John was just sixty and had battled some health problems. I liked and respected John Tries enough that once I was elected governor I appointed him secretary of the Department of Employment Relations. You log the kind of miles together in a campaign together that we did, and you feel a kinship. John’s memorial was at Turner Hall in Milwaukee. They served Beck’s, his favorite beer, and played Jimmy Buffett songs.

While John and I were bouncing around the state, we also managed to get a small campaign office open in Madison. Jerry Mullins was a businessman who owned quite a bit of property in downtown Madison, including the Park Motor Inn, later the Inn on the Park. He didn’t want to contribute to my campaign, but he liked the idea of a Republican governor. He said there was a basement office in a building adjacent to the hotel that we could use if we cleaned it up. It took some cleaning. We didn’t have any kind of storefront presence—you entered from a side door—but the place had its advantages. Ave Bie and Diane Harmelink could walk across the street from the capitol on their lunch hours or after work, and it was also close to Jim Klauser’s law office. At first Klauser stopped by once a week or so to check the books, but then, as I had hoped might happen, he got more involved despite himself.

One spring day—it was probably late April—we were both in the campaign office one noon when Jim suggested we go next door to the Park Hotel coffee shop for a hamburger. After we ordered, Jim said he thought the campaign needed to bite the bullet and do some heavy spending on advertising leading up to the state Republican convention in Milwaukee in early June. He said we had around $100,000 on hand.

“How much do you want to spend?” I said.

“All of it,” Jim said.

I’m sure I gave him a look. Klauser explained that he felt we needed to win the straw poll at the convention. Despite my statewide grassroots efforts over the past several years, some of the big-money Republicans, the country club Republicans, were either backing Jonathan Barry outright or taking a wait-and-see position. Jim felt a big win for us at the convention would pop Barry’s balloon. And if we won—even though the straw poll was not a formal endorsement—money would not be an issue. We’d be able to raise money. If we lost, well, at least we had given it our best shot.

We didn’t lose. We spent all but a few hundred bucks on a radio and TV blitz, and even though some party regulars tried to sabotage me—they moved the straw poll to Sunday, because some of my rural supporters had to leave Saturday night—we won big. I got 62 percent in the straw poll. Barry got 20. Many of our people stayed an extra day. There was a backlash against the effort to stack the vote against me.

The radio and TV campaign helped, too, but Klauser was not happy with the advertising firm we were using. I found that out a short time later, after giving a speech at the La Crosse Club. I remember a couple of things about that night. Jerome Gundersen and Charles Gelatt, two of the leading citizens in La Crosse, were in attendance. Gelatt approached me after the speech, shook my hand, and said, “I really like you. How much can I contribute to your campaign?”

“Well,” I said, “you can contribute $10,000. That’s the individual limit.”

He was shocked. “I’m not giving you that much!” he said. He shook his head. I don’t know why he even asked me. In the end, I think he wrote me a check for $1,000.

At some point I looked across the room, and there was Jim Klauser. That was unusual. Klauser didn’t get out of Madison much. He said he needed to talk to me. I was going to catch a plane to Superior to give a speech the next morning, and Jim said he would walk me to my car, which he did.

“Good speech, Tommy,” he said. “I wanted to let you know that we released most of the campaign staff today.”

I stopped walking and looked at him. I was shocked.

“You campaign, and I’ll take care of it,” he said. As it turned out, it wasn’t everybody. But a couple of things were going on. Jim was unhappy with the quality of our television spots in the run-up to the convention and went so far as to change the imagery in the last six or seven seconds. They had me looking funereal, Jim said. He found something brighter and spliced it in at the last minute, before the spots aired. Klauser was also unhappy with our campaign manager. They had tussled over the organization of the field staff. Klauser wanted it more hands-on, and the guy said, “I talk to them on the phone. It works.” Jim told me he was intending to fire him, but never got the chance. It turned out the campaign manager was in a romantic relationship with the head of our campaign ad agency. When Klauser said he was changing agencies after the convention, the campaign manager said, “Then I quit.”

Klauser was running things anyway by then, and he was tough. Around this time, one of our fundraisers made the mistake of telling Jim she was wasn’t going to turn over the money she had raised until she was paid. “That money is not yours,” Jim said. “If it is not in the Madison office by noon tomorrow I will get an arrest warrant from the district attorney.” She brought it in. Klauser paid her, and fired her.

We could get by without any particular fundraiser, but we needed a campaign manager. Klauser had talked to Gerald Whitburn, who was involved with Kasten’s Senate reelection campaign, and Whitburn had suggested we get in touch with a guy named Robert “Buzz” Buzinski, a Wisconsin native who had worked as a field representative for the Republican National Committee in states across the country. Klauser flew to Washington to meet with Buzinski. It was almost like destiny. They were having lunch in a D.C. restaurant when a camera crew from a local TV station showed up and said they were trying to do a piece on the “entertainment deduction” on tax returns, which had become controversial. The three-martini lunch was on the way out. The TV crew offered to buy Klauser and Buzinski martinis if they could take some shots of them sipping from the glasses. They didn’t have to ask twice. Jim and Buzz, as it happened, both enjoyed martinis. Buzz signed on to the campaign.

We still didn’t have much staff, or money either, but we gained momentum as the summer went on. Our campaign circulated a three-page memo that pointed out how liberal Jonathan Barry had been during his many years as a Democrat. The ultraliberal Capital Times had given Barry its third highest score out of ninety-nine members of the assembly in assessing his votes on select key issues. The memo was pretty devastating—true, but devastating—and Barry was outraged. It was while he was addressing it in an interview with the Milwaukee Sentinel editorial board that Barry called me “a two-bit hack from Elroy.” I think he knew he was in trouble.

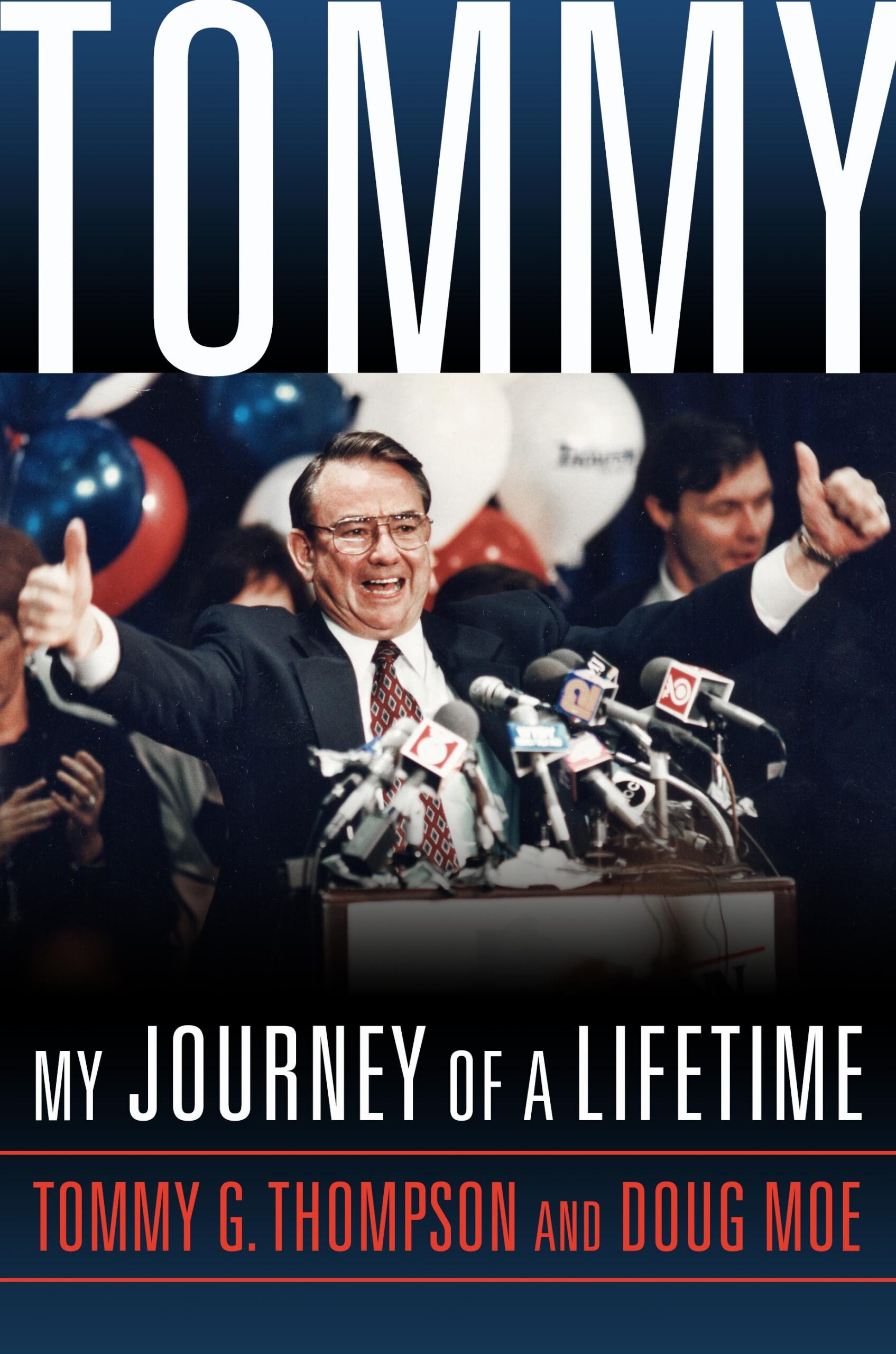

By the day of the primary—September 9—I was feeling confident we would win. Sue Ann and I had dinner that night at the University Club in Milwaukee with Jim and Shirley Klauser and John and Peggy MacIver and afterward went to the Astor Hotel, where the victory celebration was being held. The early numbers were very positive and Klauser was telling me I needed to talk to the television reporters even though my opponents hadn’t conceded yet. I wasn’t sure, but Jim insisted. It worked out well because at one point during the interview, Tony Earl came on and we were together via a split screen. Tony congratulated me and said he was looking forward to the campaign. It was a classy thing to do but a bad move from the standpoint of political strategy: it served to put me on equal footing with the governor. I held my own in the conversation. I think maybe Tony and his people were relieved that Jonathan Barry didn’t win the Republican nomination. They had become obsessed with him, and I was an afterthought. It was probably why their campaign didn’t advertise for several weeks after the primary, another terrible move in hindsight. They still weren’t taking me seriously.

That night at the Astor, after Jonathan and the others had called to officially concede, I addressed my supporters and pointed out that there was still much work to do. “We’ve won the pennant,” I said. “We are now moving on to the World Series.”

They liked that.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said, “we are going to sweep the Series.”