The following is an excerpt from “On the Capitol Beat: The scoop on Wisconsin’s capitol press corps,” by Jillian Slaight included in the 2023-24 Wisconsin Blue Book. The Blue Book will be fully available online the week of Sept. 18. Direct any inquiries to lrb.reference@legis.wisconsin.gov

Section IV: The Place

Although plans for the capitol that were drawn up in 1909 contained a dedicated press space, it appears this room, which was adjacent to the assembly parlor, was never used as intended. Reporters remained nomads in the building they covered daily. That ended in 1947, when Senate Joint Resolution 20 provided that Room 204 S, formerly a men’s restroom, be made available “for use as a press room during the 1947 legislative session.”

The state would provide surplus tables, chairs, and rugs, and reporters would be held responsible for any damages to the room or its furnishings.19 This space served as the pressroom until 1971, when reporters relocated to 217 SW, a circular room between the senate and assembly chambers. Later renumbered 235 SW, the same room remains their home base today.

>> WisPolitics is now on the State Affairs network. Get custom keyword notifications, bill tracking and all WisPolitics content. Get the app or access via desktop.

In their interviews with the LRB, reporters described the pressroom as more than a physical space; it facilitates effective reporting, encourages connections with elected officials, and creates a sense of community among the press.

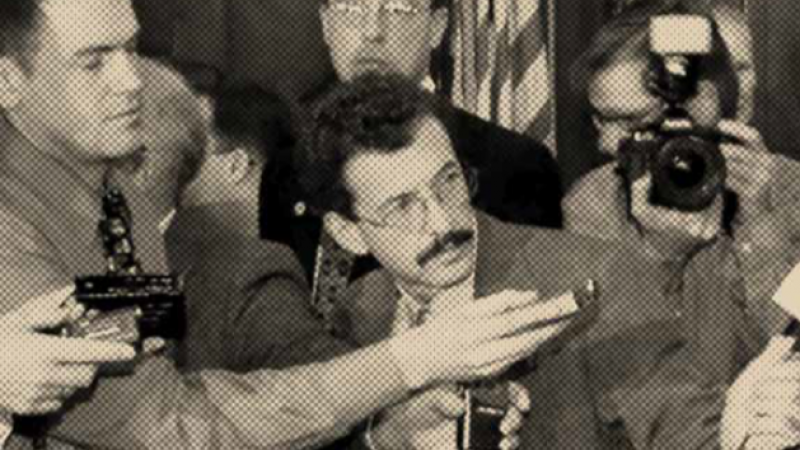

Until the 1990s, when the pressroom was remodeled as part of the capitol renovation, the space was cramped and chaotic. Lean back too far, and Steve Walters might collide with fellow Sentinel reporter Amy Rinard; open the door too hard, and he might hit Joanne Haas of UPI. Workspaces were separated by partitions “piled high with materials that could easily go up in flames,” making the room a veritable “fire trap.” Reporters’ smoking habits—from Stan Milam’s cigarettes to Neil Shiveley’s cigars and Dick Wheeler’s pipe—only exacerbated the problem. “Everybody smoked,” Milam recalled. “It was a cloud in there.” Ultimately, 1999 Wisconsin Act 72 prohibited smoking in the state capitol building, although most reporters had ceased smoking inside by that time.

Heat posed another significant hazard. Before air conditioning was installed in the early 1990s, the pressroom would become sweltering, especially as the afternoon sun poured in through the tall windows. Amy Rinard would escape to the State Law Library, just above the State Supreme Court chambers, to bask in its air conditioning. Art Srb reportedly tried to beat the heat with a large, loud, and unwieldy oscillating fan nicknamed the Gerald Lorge Memorial Fan after the longtime (and, at the time, still very much alive) state senator. Stan Milam remembered one especially hot day when everyone in the pressroom was struggling to file stories on deadline. “All of a sudden,” he recounted, “Art starts screaming . . . [T]he Gerald Lorge Memorial Fan had caught his pant leg! And it was eating up his trousers! And Art is kicking this thing, and he’s still typing. He had a deadline. So he’s fighting off the Gerald Lorge Memorial Fan and typing at the same time.” A hodgepodge of surplus and scavenged furniture reinforced the pressroom’s chaotic atmosphere. “Before the capitol renovation, the furniture looked like what’s on the curb at hippie Christmas,” John Powell said, referring to the profusion of castoff furniture in Madison every year at the end of student leases. Amy Rinard recalled working on a green metal World War II–era typist’s desk, flanked by another colleague’s ancient, oversized wooden desk and a TV stand that housed the Sentinel’s telephone and answering machine. Over time, reporters developed a knack for “scavenging furniture from the hallways.” To Powell, the atmosphere was a point of pride: “Some of us . . . were really proud of it. That we were not feathering our nests . . . [and] that this was basically hand-me-down furniture and a place to work, which is the image that I think most of us wanted to project.” Since the capitol renovation, the room now boasts uniform desks and chairs, but retains a lived-in feel: “Reporters are not the neatest,” Jason Stein conceded. “It’s not like an army barracks in terms of being spick-and-span.”

Many reporters told the LRB that the pressroom—rather than their outlet’s offices or newsroom—served as their home base. As Jason Stein put it, “I tried to be at the capitol more because I felt that that was where I . . . would be most likely to learn news relating to state government.” Long before they became available online, legislative materials—from press releases to service agency reports—would be printed and delivered to pressroom mailboxes. Amy Rinard associated certain sounds with Legislative Fiscal Bureau reports: “They’d go thunk, thunk, thunk, thunk And you’d go, ‘Oh, that sounds like news.’”

Working from the pressroom also granted reporters, especially those from the Milwaukee outlets, an opportunity to work independently from their editors. Steve Schultze explained that while Journal editors frequently telephoned, “You felt like you were more on your own and didn’t have people breathing down your neck.” Amy Rinard agreed: at a substantial distance from the Sentinel newsroom, “you couldn’t be micromanaged.”

Autonomy from editors came at the cost of unpredictability because, as Rinard put it, “That room was everybody’s room. And whatever was going on in there, we weren’t in charge of it.” Legislators and cabinet secretaries sometimes appeared in their workspace without warning. One day, Rinard was finishing a story on deadline when Governor Thompson and Department of Administration Secretary Jim Klauser entered the pressroom, armed with “a handful of tiny plastic shot glasses and a bottle of Schnapps or something.” She had filed and sent her story when an editor called with a question. Upon hearing “raucous noise” in the background, the editor asked, “Are you in a tavern?” to which she replied: “Well, no . . . I’m in the capitol pressroom.”

Still, most interviewees cited that spontaneity as a benefit instead of a downside. For decades, the pressroom has enabled in-person interaction between reporters and policymakers. As Steve Walters put it, “When a cabinet secretary is angry at what just happened at joint finance and she or he walks into the pressroom, it’s an instant news conference.” Working from the pressroom might also mean running into legislative leaders on the way to or from the restroom—or sampling the spoils of Representative Joel Kleefisch’s latest hunting trip.

In addition to access to lawmakers, interviewees cited the pooled expertise of the press corps as another benefit of working from the pressroom. Several recent reporters described their colleagues in the press corps as an essential sounding board. “We kind of have each other’s backs,” Scott Bauer explained, answering questions like, “Hey, did that ruling say what I thought it did? Am I understanding this correctly?” Sometimes, cooperation might mean putting Legislative Fiscal Bureau Director Bob Lang on speakerphone to gain clarity on a difficult-to-understand budget provision. This kind of collaboration prompts some reporters from different outlets to consider each other as colleagues. “To me,” Molly Beck commented, “it feels like a regular newsroom, even though we don’t technically work with each other.” On session days, reporters even coordinate coffee runs and takeout orders. Still, this spirit of camaraderie has its limits, as Beck acknowledged, “We’re competitors at the end of the day.” Or, as Scott Bauer put it, “If I get a hot tip, I’m not going to be like, ‘You won’t believe what I just heard from [Speaker] Robin Vos.’” And as many interviewees acknowledge, keeping information from competitors poses one of the great challenges of working from the pressroom. “We’re in a round room with a high ceiling, and everything bounces,” David Callender explained. “You’re going to hear each other’s phone calls.” Callender operated on the principle that a reporter should not act on an overheard scoop—but he and other reporters took no chances that a scoop could be overheard. “There used to be a pay phone down on the ground floor of the capitol, and you would go to the pay phone to call the [newsroom] desk and let them know what you had coming.” Former Milwaukee Sentinel bureau chief Steve Walters agreed that fierce competition necessitated covert phone calls from the first-floor pay phone: “It was a close-knit community. But when I was paid according to how often I beat the Journal, you just couldn’t share any secrets in there.”

Technological advances have eased this problem a bit. Jason Stein spelled out a hypothetical in which a reporter receives a tip about an amendment poised to break a budget impasse: “Now you could send an email, you could call by cell phone in the hall, you could Slack them, whatever. There’s a million ways to do it.” But efforts to maintain privacy can be unsettling. Jessie Opoien mentioned how hushed conversations between former Journal Sentinel reporting partners Jason Stein and Patrick Marley would prompt her gnawing curiosity: “They would just get really quiet. And I’d be like, ‘What are they doing? What do they have? .. What am I going to have to chase later today?’”

Read the full article, including the “Safeguarding the press room” sidebar, here.